Within 24 hours of Kasabian singer Tom Meighan’s announcement that he would be stepping back for “personal reasons,” he was at Leicester Magistrates Court pleading guilty to one count of assault by beating (common assault) on his ex-fiancee.

The details of the offence as they are reported – that he was drunk, knocked her down, attempted to strangle her, pushed her into a hamster cage and threatened her with a pallet, and most prominently, that he did all of this in front of a child – are serious.

A number of people are, quite reasonably, asking how it might be that he didn’t go to prison.

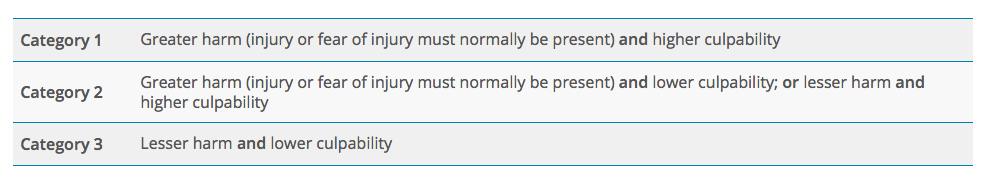

The sentencing guidelines on common assault require that the judge first consider the “offence category.”

There seems to be little doubt that in this case there was greater harm (it was described as a sustained attack) and higher culpability (strangulation is understood to signify an intention to commit greater harm than may in fact have resulted), placing it firmly into Category 1, the most serious category.

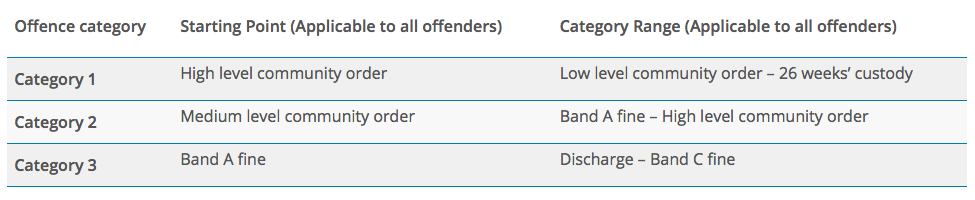

The court then moves on to the starting point and category range.

The starting point for a Category 1 offence is a high level community order, which is then adjusted up or down depending on aggravating and mitigating factors.

Aggravating factors will include that the offence was committed in the presence of a child and while under the influence of alcohol. Mitigating factors would have been remorse and his claimed commitment to addressing an alcohol dependency. Add to that the credit he is given for a guilty plea, and the adjustment is up and back down again to the starting point for a Category 1 assault.

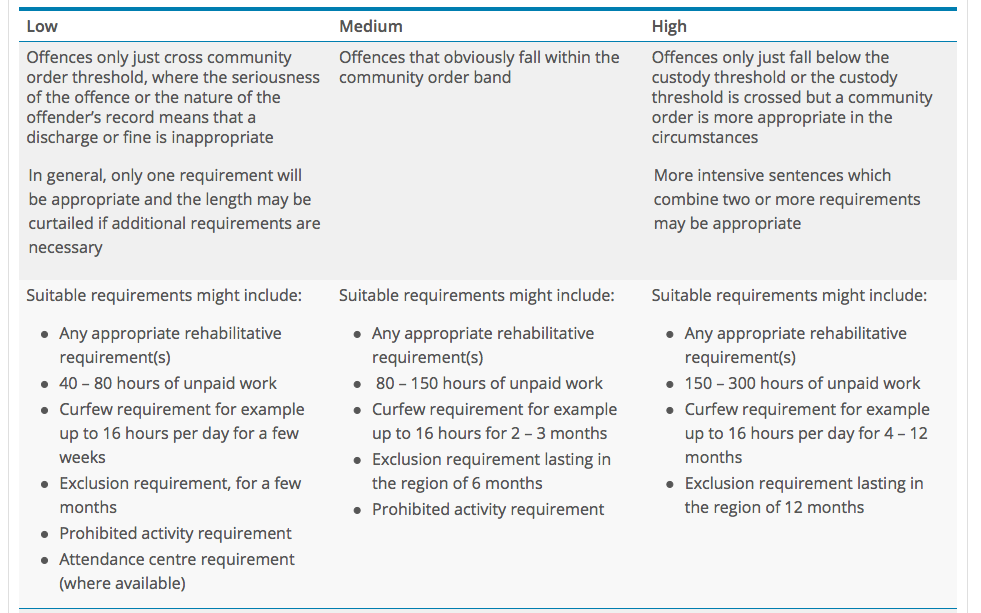

This table sets out what is meant by a ‘low’ ‘medium’ or ‘high’ level community order. Meighan was given 200 hours unpaid work and a rehabilitation requirement, placing this at the upper end of the high level community order band, narrowly missing the custody threshold.

All that this means, of course, is that the sentence is in line with the Sentencing Guidelines. It doesn’t mean that the Sentencing Guidelines are beyond criticism.

The Centre for Women’s Justice has campaigned for non-fatal strangulation to be made a specific crime, as it is under-charged when treated as common assault, and other organisations have campaigned to make misogyny a hate crime. It may well be that sentencing in domestic abuse cases needs reform – but as of today, these are the guidelines that continue to apply, and may go some way to explaining why cases like these continue to attract non-custodial sentences.