This is a blog about sentencing, and outrage, and outrageous sentencing.

In particular, it’s about this case of sexual assault perpetrated by a stranger, reported in the Mirror as “Dad who attacked woman walking home at night avoids jail as he ‘would lose his job.’”

The facts are thrown into particularly sharp relief this week, in the wake of the abduction and murder of Sarah Everard. The defendant, Javed Miah, walked behind the victim and bumped into her, asking her the time. After following her for a minute, he groped her bottom, pushed her to the ground, and moved his hand from her crotch up to her chest. The victim managed to connect an emergency SOS call on her mobile phone at which point he ran away.

Miah was given a six month sentence, suspended for two years. He will also have to complete 250 hours of unpaid work, complete the sex offenders rehabilitation programme, and sign the sex offenders register for seven years.

Women are justifiably outraged. How can a man push a woman to the ground, commit a sexual assault, seemingly intent on worse and yet walk free from court?

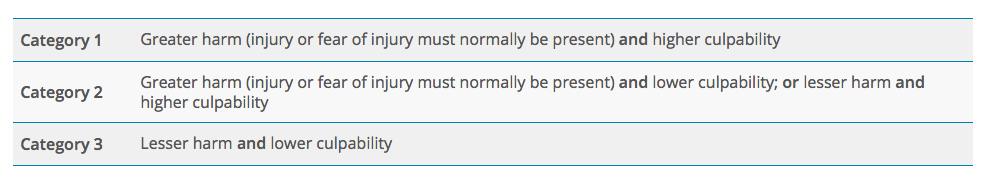

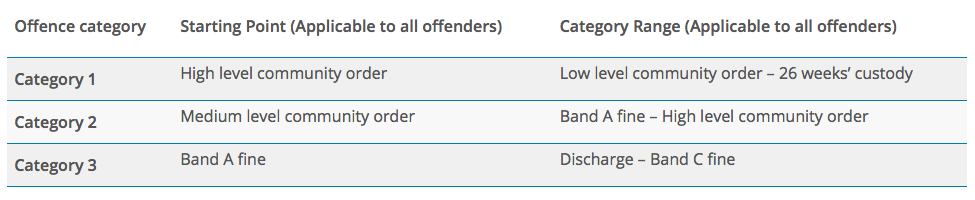

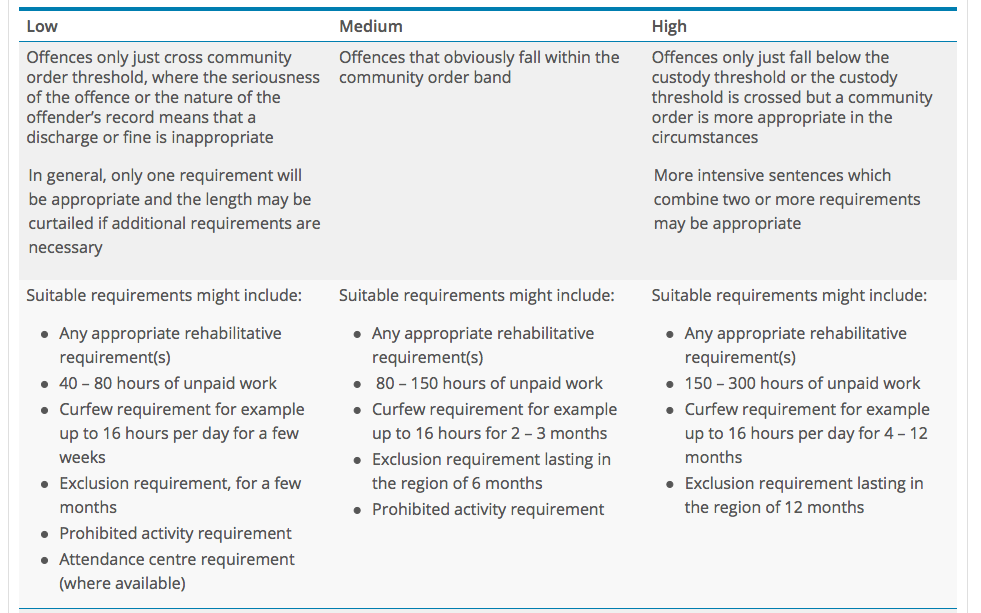

Other commentators can point you towards the Sentencing Guidelines and point out that the judge has followed them. The Mirror reported that the judge called the attack ‘sustained.’ That would make it a Category 2, Culpability B offence, carrying a one year starting point with a range of a community order to two years custody. With both the logic and the emotion of a Sudoku puzzle, the starting point of one year is then adjusted up for location and timing (alleyway, after dark), then down for previous good character and remorse, ending at a 9 month sentence. A further 30% off is applied for a guilty plea, bringing it down to six months. The judge must then consider mitigation and whether or not the sentence can properly be suspended. Any sentence of 2 years or less is capable of being suspended – and there are good reasons for this: if someone loses their home, job, relationship and future prospects they are more, not less, likely to reoffend. Feed the data here into the OASys machine and we have a defendant who has a secure relationship – ding! – with a job – ding! – and a home – ding! – and children, meaning community ties – ding! – which all feeds into the assessment of a low risk of reoffending.

So yes, assuming from the limited information in the reports that it was correctly categorised, the magistrate has applied the guidelines correctly. The defendant pleaded guilty, so we don’t even need to get into whether the prosecutor has done their job well: plainly they have. Defence lawyers are often blamed for ‘getting their client off the hook,’ but since this defendant had pleaded guilty, we can blame the defence for nothing more sinister than effective mitigation, which is the right of the most egregious criminal in the land. And of course, it would be absolutely wrong to suggest the judge was entitled to sentence the defendant for what he (probably) would have done if not for the victim’s actions, rather than for what he did do. We do not sentence people for things they didn’t do – even if we think they might have done had they had the opportunity. This is fundamental to the rule of law.

And yet.

The purpose of this blog is not to reassure readers that the system is infallible. It is to make plain that the disquiet felt by women at sentences like this is not because women have failed to understand how the guidelines work, but because the guidelines do not reflect the terror that this type of offending causes to women going about our daily lives. We can reassure readers that such sentences are not the result of outright bias or corruption – but we would, ourselves, prefer an assurance that the Sentencing Guidelines will be updated and improved.